The Black Lives Matter Street Mural Map documents and visualizes street murals with the goal of understanding these artworks and their viral spread, showcasing (especially black) artists, and holding communities accountable for change beyond paint on pavement.

Following the murder of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police in the summer of 2020, a vital trend propagated throughout the country and even internationally as communities—big and small, urban and rural, sanctioned and unsanctioned—engaged in a memetic dialogue of installing and remixing anti-racist artworks on their streets. The Black Lives Matter Street Mural Map—an open research project created as a collaboration between the Kennedy School’s Belfer Center (Stephen Larrick) and metaLAB (at) Harvard & FU Berlin (Kim Albrecht)—documents these works as a research database and as a map featured in the Designing Peace (2022 – 2023) exhibition at the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Museum of Design in Manhattan.

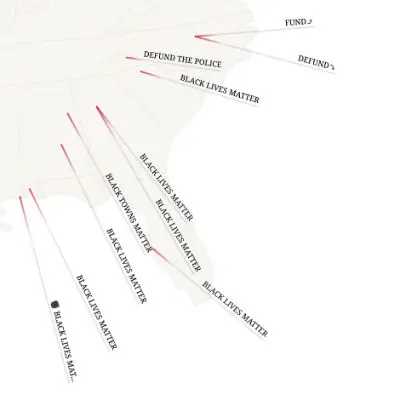

Almost no murals with the phrases "defund the police" or "reparations" were sanctioned and nearly all were immidately removed. Notable exceptions included an officially permitted mural in Berkeley, CA reading "REPARATIONS NOW!" and an unsanctioned mural in Durham, NC reading "DEFUND" that was allowed to remain on the street in front of the police station for over a year due to "special circumstances".

While many communities with histories of police violence participated in the trend, mural locations sometimes do not correlate with locations of fatal police encounters.

Oakland was the first mural to replicate the standard yellow traffic paint style of Black Lives Matter Plaza in Washington DC. Over 65 murals used this style. Oakland notably added a hashtag ("#") to their mural, alluding to the online, as well as physical nature of this viral "meme".

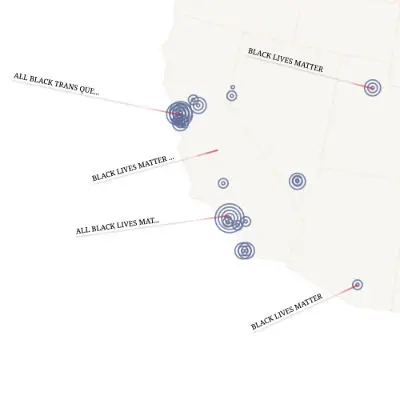

Murals were installed even in communities without a significant Black population, prompting conversations about broad appeal/participation vs cooptation. This phenomenon can be seen in Vermont, a state with a high number of murals, despite having the lowest percentage of Black population in the country.

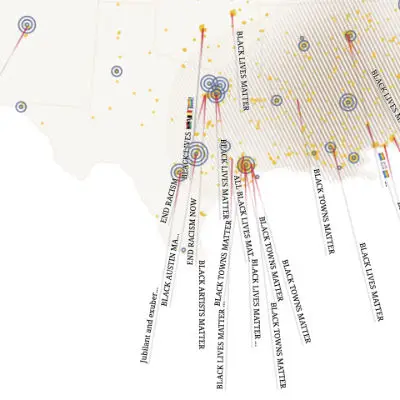

Charlotte, NC was the first city to put a twist on the DC mural by commissioning a different artist to complete each of the letters in BLACK LIVES MATTER. Dozens of cities would adopt this approach, showcasing (and paying) hundreds of often black community artists. A mural in Austin embody's this same trend reading BLACK ARTISTS MATTER.

At least 27 murals were installed on Friday, June 19th, 2020 during the Juneteenth holiday with another dozen installed on Saturday or Sunday that weekend.

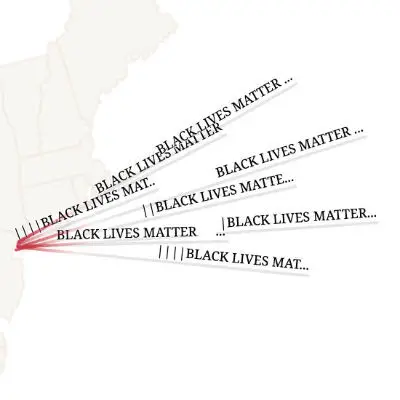

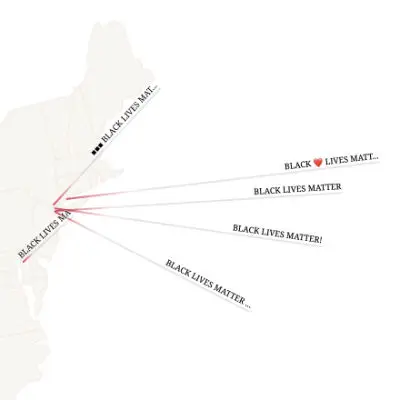

New York installed 9 murals, the most of any city.

The form of the BLM mural evolved to take on a variety of social justice causes from LGBTQIA rights, feminism, prisoners rights to housing justice to voting rights to educational justice to immigration justice to public health and the list goes on.

Trends developed within the trend of BLM murals. In one prominent example, a coalition of "Freedman Settlements", historic communities founded and run by Black americans during a time of segregation and racial terrorism, created "Black Towns Matter" murals, such as the one in Independence Heights, a former Black Town since incorporated as a neighborhood of Houston. Visit blacktownsmatter.org

Many unsanctioned murals were removed by government officials, often to the dismay of protesters. This was the case in Tulsa, OK where the BLACK LIVES MATTER mural installed on Greenwood Ave, the historic "Black Wall Street" and site of the infamous Tulsa Race Massacre.

While the trend started in big cities like Washington DC, many small towns and even rural communities participated as well. This trend can be seen in the small mountain town of Crested Butte, CO, with population just over 1,300.

Over 15 murals remixed the "yellow" aesthetic of DC's mural, instead adopting the red, black, and green color scheme of the Pan African flag. A mural in front of Dallas City hall was the first to use these colors.

This project is powered by the Black Lives Matter Street Mural Census, an open database with information gathered from a variety of sources, including from crowdsourced contributions. As a result, some data is incomplete or may contain errors. If you have an additional mural to submit we encourage you to do so here, and if you notice any errors you can submit changes by clicking on the relevant mural and selecting "submit changes to the data."

Stephen Larrick, 2022, Black Lives Matter Street Mural Census, Belfer Center, Harvard Kennedy School

D. Brian Burghart, 2022, Fatal Encounters, fatalencounters.org

U.S. Census Bureau, 2020, Census Redistricting Data

Visualization and Design:

Kim Albrecht, metaLAB (at) Harvard and Freie Universität Berlin

Data Collection and Project Initiative:

Stephen Larrick, Belfer Center, Harvard Kennedy School

Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School